Atacama Desert, Chile

In 2013, I spent a few days in the Atacama Desert exploring a variety of jagged and colourful landscapes. The desert is highly popular with visitors but also important to Chile’s economy; 33% of the world’s lithium production occurs here.

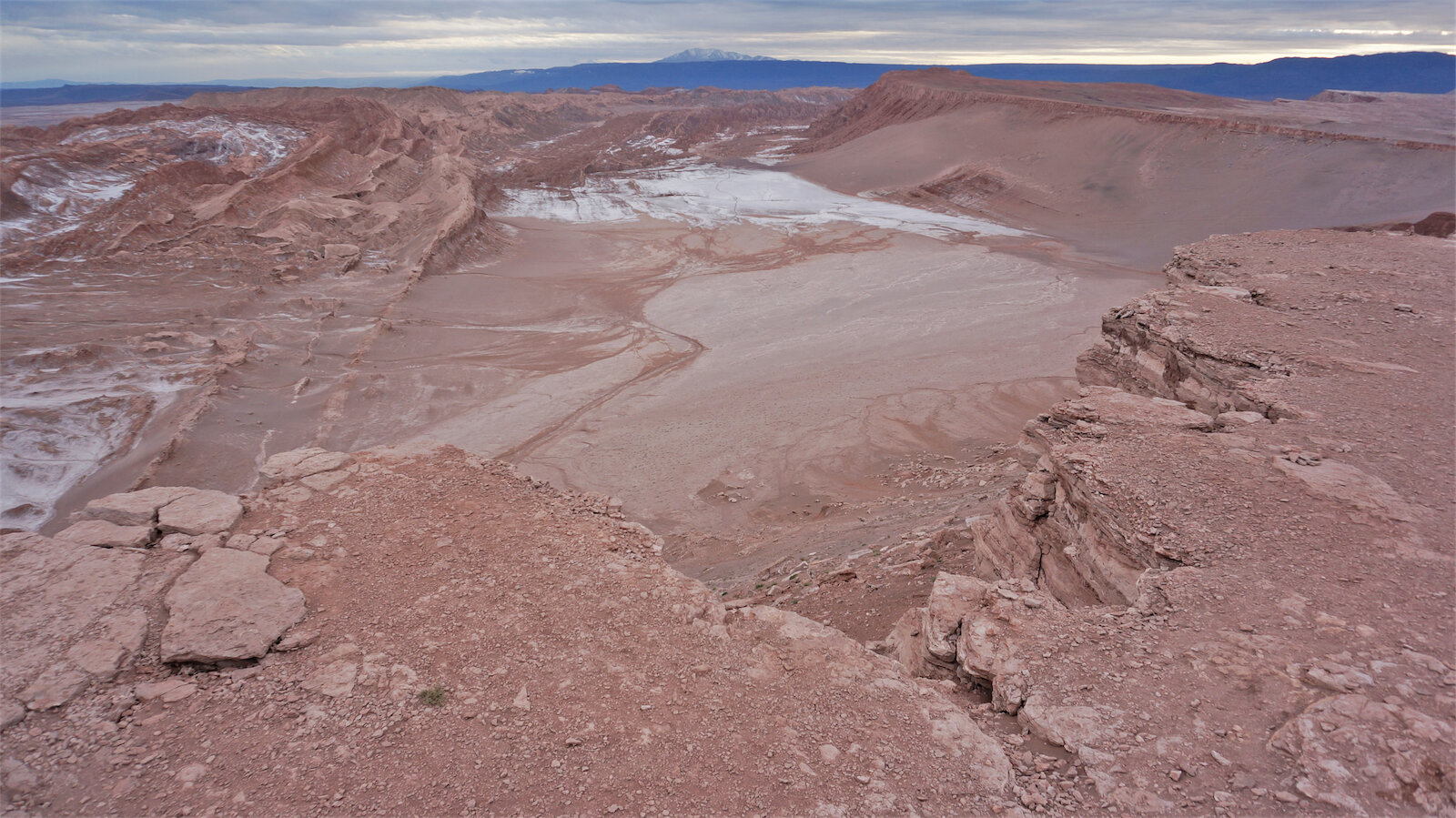

To begin, a tour through the Valley of Death took me through striking meandering salt caves. Passing in and out of the sunlight’s forays into the rocks, I observed their ridged, shining surfaces formed by centuries of evaporation. Later, the sunset over the Valle de Luna was a panoramic spectacle. Just as it faded, a deep blood red suddenly returned to undercoat the clouds.

Travelling towards a large salt lake more than 4,000 metres above sea level, I was stopped at the entrance to its enclosing national park and asked to watch a video on the importance of protecting Chile’s wildlife. Having seen unspoilt land eradicated to develop expensive private properties in areas throughout Chile on my previous travels, it feels unclear what the authorities’ priorities really are. Nonetheless, Laguna Chaxa and its surroundings are astounding: the wildlife reserve inside the national park is a peaceful expanse of salt rock and water, dotted with blushes of pink Andean and James flamingos and Andean avocets.

Snowfall the previous night meant it wasn’t possible to reach the Altiplanic salt lagoon, so I stop in the small village of Socaire with a church built from salt and mud. The clouds are thin but rush across the sky, providing a dramatic, shifting backdrop against the church’s centuries-long permanence on the mountain. Another humble town, Toconao, instilled in me a similar feeling of calm and awe to be where I was. Seeing every-day life occur in the heart of a landscape like this helps translate the reality of the spectacle into something even more powerful.

The following day started at 4am as I began to make my way to a field of geysers. Reaching the peak of the mountains, the stars were the clearest that I have ever seen them. I saw Orion’s arrow pointed towards Mercury, nested just above the silhouette of the Andes Mountains.

The sun had not fully risen as I reached the geysers, but their vapour was visible as it soared out of the freezing ground. Ignoring the signs advising against straying from the path, I wandered through the welcoming plumes into the relatively untrodden land beyond. I felt a sense of urgency reaching for my camera as I tried to make the most of the quickly rising sun.

Shallow streams of water meandered through broad tufts of dark, moss-like vegetation. Further ahead, a collection of salty rock reliefs acted as steppingstones over calmer but equally as destructive geysers. The sun rose further as I spotted a shimmering wall of steam in the near distance, but my interest is drawn aside, towards the sun’s creation of a gold and green display over the vegetated distant mountains. All of this is complemented by the course of a brilliant-blue stream flowing in the foreground.

On the route back to San Pedro de Atacama I stopped in the village of Machuca. It is similar to Toconao but about a quarter of the size. Unusually, Machuca’s church is located away from the centre of the town, with bright blue doors complementing an identical sky. The original village was built ten metres lower than the new settlement and its ruins are still visible on the side of a valley filled with natural colour. It is unclear when the original town was built, but the reason for its destruction is evident from the riverbed carving through the valley.

Taking in such a diverse landscape over a short number of days made me question if I would be able to remember it all. This was my main motivation for documenting the time so closely with photographs and writing. The genuineness of the people local to San Pedro and the respect of other explorers preserves the Atacama as one of the most special places on Earth.